Jacob August Riis was born in Denmark in 1849, and immigrated to the

United States in 1870 at the age of 21. He arrived in New York City with

no money, but like so many other immigrants, he was hoping to make his

fortune in America. Unfortunately for Riis, America was in the middle of

a depression in 1870, and many people were out of work and homeless.

Riis managed to find a few odd jobs from time to time, but was unable

to find steady work. There were many times that he didn't have enough

money for food or shelter and was forced to live on the streets. During

the winter months he couldn't sleep outside, so he had to utilize the

only option for shelter available to people at that time who had no

money - a police lodging house. They were dirty and crowded, and people

had to sleep on the bare floor, on newspapers or a plank of wood, but at

least they had a roof over their head.

After several months of hunger and homelessness Riis was in total

despair. One cold and rainy night, he sat at the river's edge and

began to contemplate suicide. After all he thought, no one would notice

and no one would care. Then, as he later wrote in his autobiography The

Making of an American (1901), a little dog who had befriended him the

day before and had followed him around ever since, "crept upon my

knees and licked my face and the love of the little beast thawed the

icicles in my heart." Well, at least the little dog cared about

him. The little dog's affection lifted his spirits enough so that he

was able to go on.

Later that night, Riis was forced by the cold to take refuge in a police

lodging house. He tried to sneak the little dog in under his coat, but

the desk sergeant saw and made him put it outside. As he slept, Riis was

robbed of a small gold locket that he had saved and treasured as a

memento from home. He complained to the desk sergeant who got very

angry, accused Riis of being a liar, and ordered one of his officers to

throw him out.

The little dog had been waiting outside the door all night. When he saw

Riis being pushed out the door by the policeman, he bit the officer on

the leg. The policeman grabbed the dog and smashed his head against the

steps.

This incident could have been the thing that finally pushed Riis over

the edge, but instead it transformed his despair into anger. He vowed

that somehow he would find a way to avenge the death of that little dog.

Soon thereafter he began writing a book he called Hard Times.

His "hard times" continued for a while, but one day his life

was changed forever when an acquaintance who ran a telegraph school told

him about a job. He said a man who ran a news agency was looking for a

"bright young fellow whom he could break in" and offered to

write a letter of introduction for him.

Riis was hired by the agency and soon demonstrated a talent for writing.

Then he acquired a camera and taught himself photography. By 1877, his

reputation had grown so that he was hired as a police reporter for the

New York Tribune and the Associated Press. His beat was Police

Headquarters on Mulberry Street, one of the worst slums in the city. In

1887, he read about the invention of the magnesium flash and he was one

of the first photographers to use flash powder. That enabled him to

photograph the tenement interiors and the streets and back alleys of the

slums at night. In 1888, Riis left the Tribune and was hired as a photo

journalist by the New York Evening Sun where he began his crusade in

earnest to publicize the plight of the poor.

Riis' work while at the Sun and his first book, How the Other Half

Lives; Studies Among the Tenements of New York, published in 1890, were

an international sensation. His evocative writing coupled with his

revealing photographs were a powerful indictment of society's

indifference to the plight of the poor.

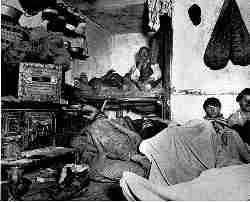

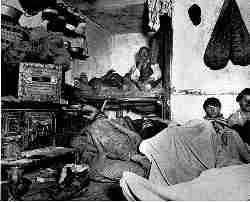

Inside a tenement room

Riis was an advocate for the immigrant poor, the oppressed, the

exploited, and the downtrodden. He wrote that the poor were victims of

economic slavery and that they were the "victims rather than the

makers of their fate." He also believed that poverty and misfortune

were responsible for criminal behavior. He blamed much of the misery and

crime present in the slums on the greed of landlords and building

speculators. Riis called it "premeditated murder as large-scale

economic speculation." His reporting inspired shock and horror

among New York's rich and middle classes.

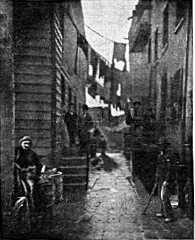

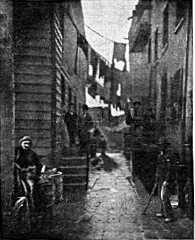

Bandit's Roost

His book also captured the interest of the New York Police Commissioner,

Theodore Roosevelt, who would later become governor and then the 26th

president of the United States. Riis took Roosevelt with him on his

forays into the dark corners of the city. When Roosevelt became governor

he closed down the police lodging houses, and led the fight to enact

many reforms. Roosevelt called Riis "the most useful citizen of New

York."

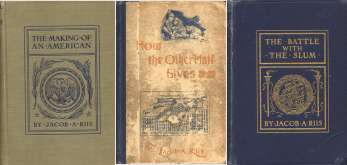

Riis continued to write and lecture on the problems of the poor for the

rest of his life. He wrote several other books; including Children of

the Poor (1892), Out of Mulberry Street (1898), The Battle With the Slum

(1902), Children of the Tenement (1903), and his autobiography, The

Making of an American (1901).

The Making of an American

How the Other Half Lives

The Battle with the Slum

Riis conducted "magic lantern" shows in cities all over

America, where he projected his photos onto a large screen. One

newspaper reported, "His viewers moaned, shuddered, fainted and

even talked to the photographs he projected, reacting to the slides not

as images, but as a reality that transported the New York slum world

directly into the lecture hall."

Jacob Riis has been credited with precipitating many of the reforms that

improved the living conditions of the poor during what is now known as

the Progressive Era. Health and sanitation laws were passed and

enforced. Landlords were forced to make repairs and improvements. Laws

were passed requiring modern improvements to new residential

construction. The Mulberry Bend slums were eventually razed, largely due

to his efforts. He also started the Tenement House Commission and the

Jacob A. Riis Settlement House. By the time he died in Barrie,

Massachusetts, on May 26, 1914, he was known as the "Emancipator of

the Slums."

Jacob Riis, circa 1900

His work has proven to be an invaluable resource to historians and

social scientists ever since, but many of his photographs would be lost

today if it weren't for a photographer and historian named Alexander

Alland. In 1946, he searched for and found Riis's original glass plate

negatives in the attic of the Riis family home right before it was to be

torn down. They are now part of the collection of the Museum of the City

of New York.

Riis' magnificent contributions to the betterment of living conditions

for the immigrant poor might never have happened, were it not for the

love of that little dog. He always concluded his lectures with the

declaration, "My dog did not die unavenged!" and no one will

ever disagree with that.

|