|

|

|

|

|

Boss TweedThe Plundering Politician | |

|

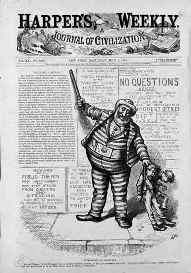

Let's stop them damn pictures. I don't care so much what the papers write about

- my constituents can't read - but damn it, they can see pictures. |

|

|

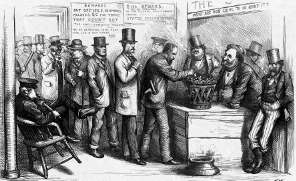

Tweed was a member of an organization called The Society of Saint Tammany, that was founded in 1789; taking it's name from the chief of the Delaware Indians. It began as a patriotic and charitable organization created by tradesmen who were not allowed to join the more exclusive clubs of the wealthy. As wave after wave of new immigrants arrived in New York City during the 1800s, Tammany gave many of them a helping hand with food, shelter and jobs. Over time, Tammany politicians built an enormous base of support by organizing immigrants into a voting bloc that could be counted upon to remain loyal. By the time Tweed came along, Tammany had already evolved into a well-oiled political machine that was known as Tammany Hall after the headquarters building that was located on East 14th Street. Tweed used the machine to facilitate graft and corruption on a scale that has never been equaled in the US.

Boss Tweed used his influence with state politicians to pass legislation that shifted power away from the state and towards New York City. He obtained passage of the New York City charter in 1870, that gave him and his cronies the final say over all city expenditures. Many upgrades to the city's infrastructure were required. New buildings, parks, sewers, docks, street improvements, and other construction projects provided ample opportunity for graft. Kickbacks were demanded from all contractors doing business with the city. Tweed and his pals used inside information on city construction projects to purchase land that they could later sell at great profit. Tweed started his own companies and then forced the city to do business with them.

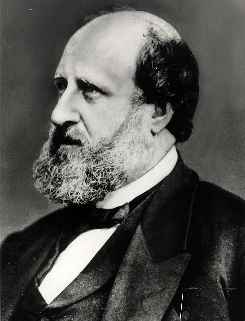

Businessmen were eager to buy influence with him and he put a price on everything. He became a director of the Erie railroad by providing "political services" to moguls Jay Gould and James Fisk. He refused to allow construction on the Brooklyn Bridge to continue until he was given a seat on the board of the bridge company. Tweed seemed unstoppable, till one lowly county bookkeeper, unhappy with his cut of the graft, provided some incriminating documents to the New York Times. The Times published a series of articles about huge cost overruns in the construction of the Tweed Courthouse. The courthouse was supposed to cost only a half-million but ultimately cost the city $13 million.

Prosecutor Samuel J. Tilden was able to trace money directly from contractors to Tweed's bank account. Tweed was finally arrested and brought to trial, but the trial resulted in a hung jury. Tilden believed that Tweed had bribed the jurors, so when he retried the case, he assigned one police officer to guard each member of the jury, another police officer to watch the first one, and a private detective to watch over all three. Tweed was found guilty of failing to audit claims against the city and convicted on charges of forgery and larceny. He was sentenced to 12 years in jail, but that was later reduced to only one year, which he served and was released. The city then sued him for $6 million. Tweed was jailed again, but he was allowed to visit his family every day accompanied by a guard. During one of those visits he managed to escape.

He was very ill in his final months and wanted to die at home instead of in jail. Tweed offered to reveal everything he knew about Tammany Hall in exchange for a parole, but his offer was rejected and he died in jail in 1878. Samuel J. Tilden's reputation as a reformer launched his political career. He was elected governor of New York and nearly won the presidency in 1876. In fact, Tilden won the popular vote that year, but lost the presidency in the Electoral College to Rutherford B. Hayes. Tammany Hall continued to control much of New York City politics till the 1920s and it was still influential in local politics into the 1960s. |

|