|

|

|

|

|

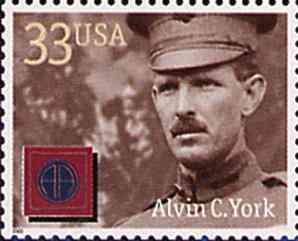

Sergeant Alvin C YorkThe Reluctant Hero | |

|

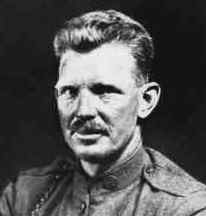

Alvin Cullum York was born on December 13, 1887 in a two-room log cabin in Pall Mall Tennessee. His father was a farmer and a blacksmith, and Alvin was one of 11 children. Like most mountain people of that time, Alvin learned to hunt at a very early age. The tall, red-headed youth was an expert shot who often participated in and won the weekly shooting matches that were held in town on Saturdays. He was a wild young man who did a lot of drinking and fighting, but in 1914, after one of his best friends was killed in a bar fight, he realized the error of his ways and converted to Christianity. York joined a fundamentalist church with a strong moral code that forbade violence of any kind. |

|

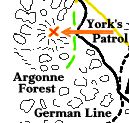

And so, when the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, York wrote on his draft notice "Don't want to fight," but he was denied conscientious objector status and drafted into the Army. During his training and before he was shipped overseas, York's commanders spent a lot of time talking to him about his beliefs and managed to convince him that going to war to save lives was a moral thing to do. He was very relieved that his moral dilemma was resolved and became an outstanding soldier. York was such an excellent marksman that he was promoted to Corporal and assigned to train other men. On October 8, 1918, in the Argonne Forest in France during the last major battle of World War I, Corporal York and sixteen other American soldiers led by acting Sergeant Bernard Early crept around the left flank of the German lines. Their mission was to capture some machine gun positions and a rail line that was supplying the German front.

York was crouching on the ground, trying to use the prisoners as cover. As he later recounted in his diary, "The Germans were what saved me. I kept up close to them, and so the fellers on the hill had to fire a little high for fear of hitting their own men." "As soon as the machine guns opened fire on me, I began to exchange shots with them. In order to sight me or to swing their machine guns on me, the Germans had to show their heads above the trench, and every time I saw a head I just touched it off. All the time I kept yelling at them to come down. I didn't want to kill any more than I had to. But it was they or I. And I was giving them the best I had."

"Suddenly a German officer and five men jumped out of the trench and charged me with fixed bayonets. I changed to the old automatic and just touched them off, too. I touched off the sixth man first, then the fifth, then the fourth, then the third, and so on. I wanted them to keep coming. I didn't want the rear ones to see me touching off the front ones. I was afraid they would drop down and pump a volley into me." York explained in his autobiography that as a boy he had learned when hunting geese in flight to shoot the birds in the rear first and work your way to the front, so that the others don't spook and scatter. A German Major who had already been taken prisoner had seen enough. He called to his men and ordered them to surrender. The 8 remaining Americans now had over 80 prisoners, but they were still behind German lines. York put the German Major at the head of the line of prisoners and held a gun on him, as he and the other American soldiers began to escort the prisoners back towards the front lines. Along the way, they came across other Germans and York would have the Major order them to surrender. Only one other German refused to surrender, so York had to shoot him. "I made the major order him to surrender twice. But he wouldn't. And I had to tech him off. I hated to do it. I've been doing a tolerable lot of thinking about it since. He was probably a brave soldier boy. But I couldn't afford to take any chances and so I had to let him have it." By the time they reached the American lines, they had 132 German prisoners, including 3 officers. A survey of the battle scene conducted by the Army a few days later, showed that York had killed 28 Germans. Word quickly spread throughout the entire Allied armies and to newspapers around the world, about York's amazing courage and how he had captured so many prisoners almost single-handedly.

The Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, General John J.

(Blackjack) Pershing called York, "The greatest civilian soldier of

the war." Pershing presented him with America's highest award for

valor; The Congressional Medal of Honor and promoted him to Sergeant.

Marshal Foch, Supreme Allied Commander said, "What York did was the

greatest thing accomplished by any soldier of all the armies of

Europe" and awarded him France's medal for bravery; The Croix de

Guerre. "It seemed as though most all of the people in the streets knew me and when they began to throw the paper and the ticker tape and the confetti out of the windows of those great big skyscrapers, I wondered what it was at first. It looked just like a blizzard." York was inundated with many offers to lend his name to commercial endorsements, but he refused them all, saying, "Uncle Sam's uniform ain't for sale." "It was very nice. But I sure wanted to get back to my people where I belonged, and the little old mother and the little mountain girl who were waiting. And I wanted to be in the mountains again and get out with hounds, and tree a coon or knock over a red fox. And in the midst of the crowds and the dinners and receptions I couldn't help thinking of these things."

In 1941, filmmaker Jessie Lasky approached York about making a movie of his life. He initially refused, but finally consented when he realized that he could use the money it would earn for him to build a school for the children in his hometown. The film Sergeant York was a smash hit and Gary Cooper earned an Academy Award as Best Actor for his laconic portrayal of York.

|

|